Shoot for Now, Ask Questions Later (Full Version)

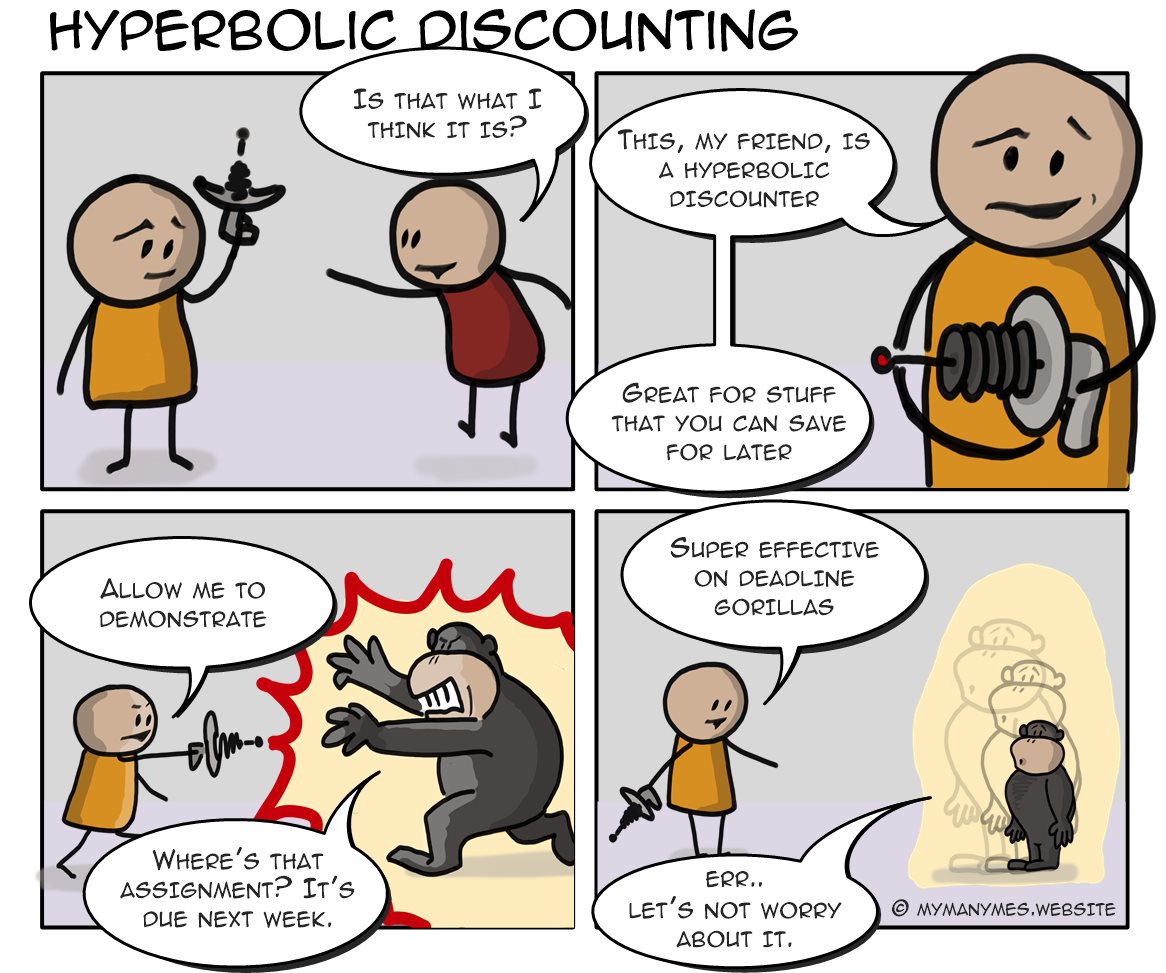

Deadline gorillas. They chase us to get that assignment done or to fill in our tax return. But unfortunately for them, we soon learn how to avoid them by applying some hyperbolic discounting. It makes the less urgent ones seem smaller and somehow less significant. It's called procrastinating.

Hyperbolic discounting is the fancy scientific name given to the way we prefer something sooner than later even if, objectively, waiting is better. It's because we don't tend to value future rewards properly and instead we are in love with the "now".

I know that hyperbolic discounting sounds like it reduces things but that's not always the case. Think of it as dividing. Dividing makes things smaller if you divide by a large number. However, once a number (such as the time you have left) becomes small enough, it makes things bigger. That's why deadlines become big and scary when you run out of time.

Impulsive people are addicted to their hyperbolic discounters and use them every chance they get. For them, life can be a rollercoaster; at times they are dodging important tasks to pursue short term distractions and at other times they rush to meet deadlines when things become urgent. Procrastination expert Piers Steel in his book the Procrastination Equation tells us that impulsiveness is the main reason people procrastinate. His equation states that our motivation to perform a task is equal to the value we place on it adjusted by its likelihood or expectancy divided by the time that we have to wait or its delay and by how impulsive we are.

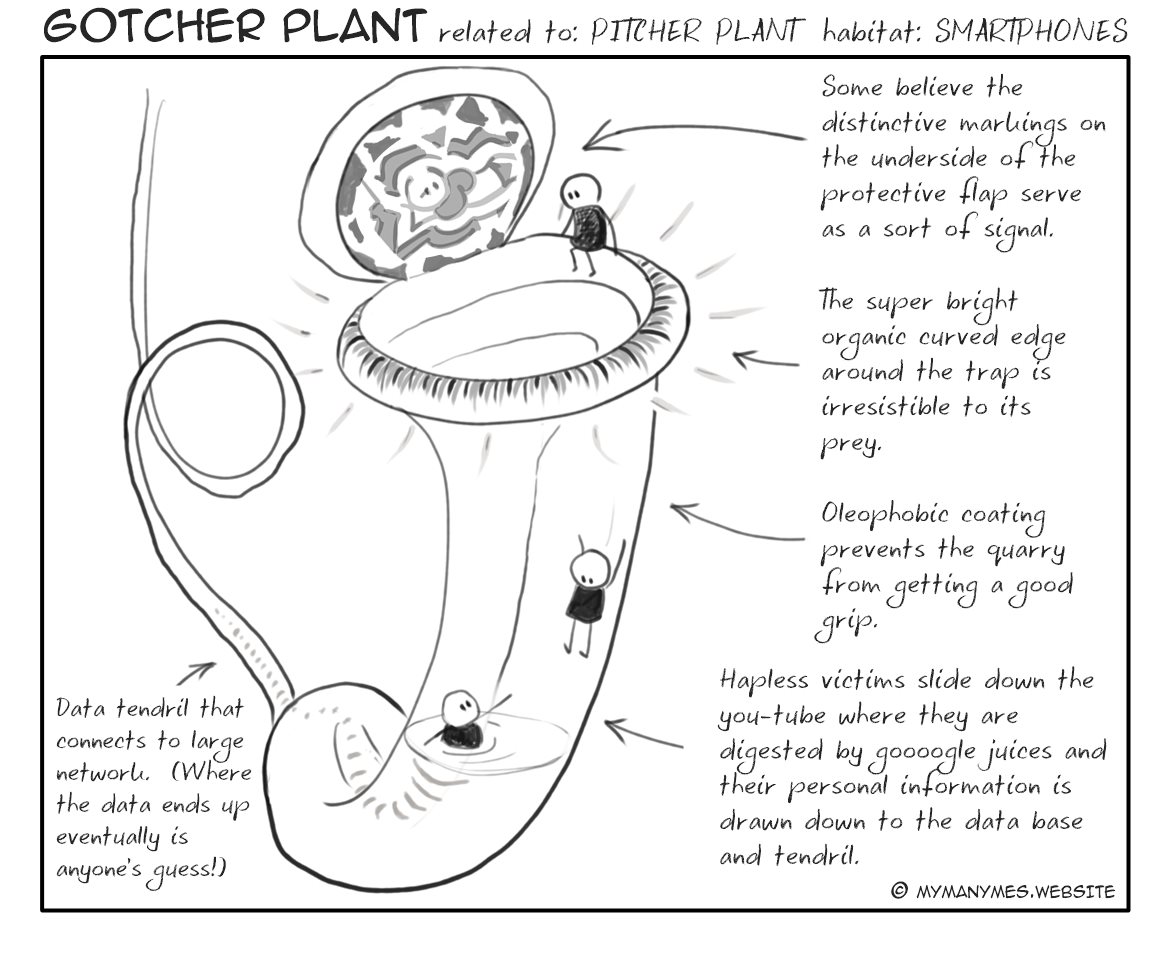

Not only do we have our deadline gorillas but we have our distraction monkeys who pull us away from what we know we should be doing. They play video games with us, they check out social media sites, or just hang out with friends. They steal our time and prevent us from working on our long term goals.

The Elephant and the Visually Impaired

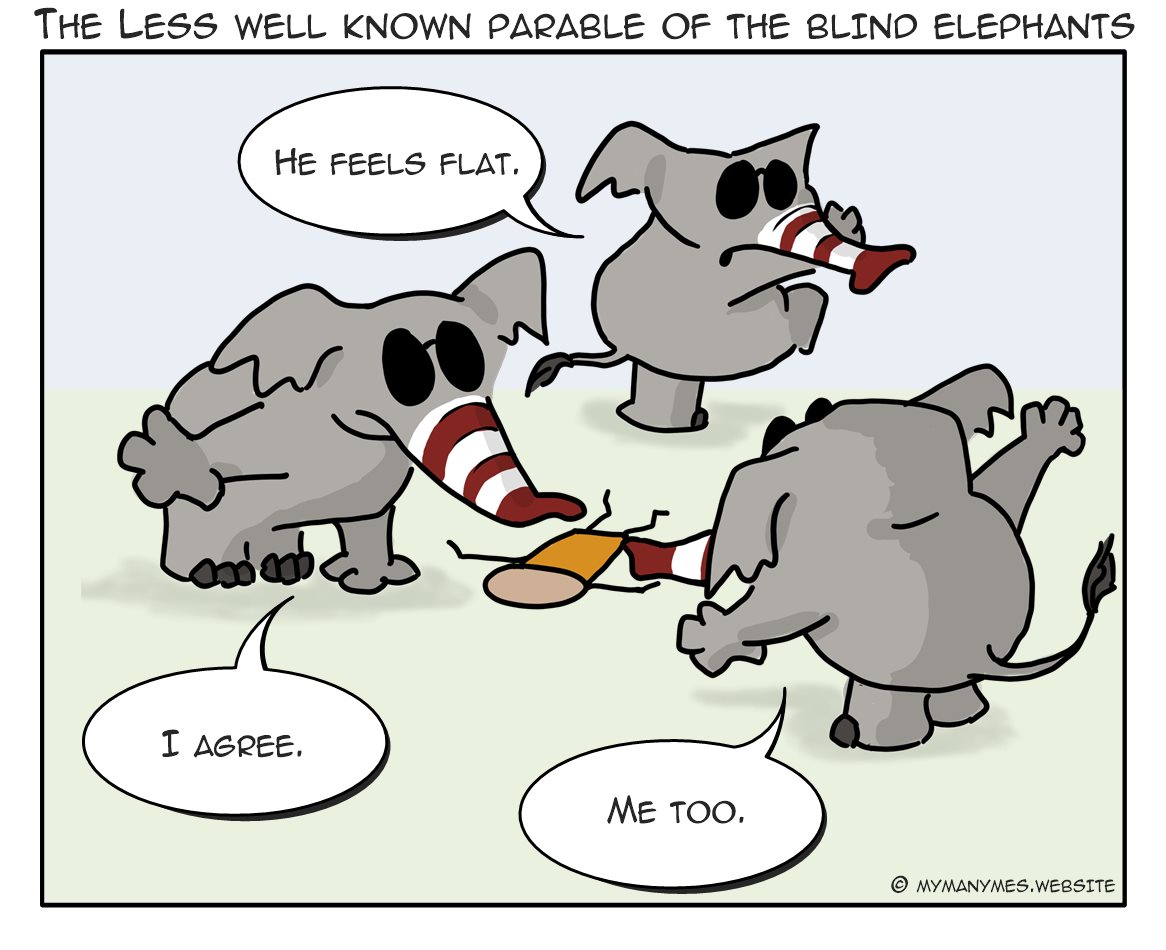

Ask one person why he or she procrastinates and you get one answer, ask someone else and you get another. This reminds me of an ancient parable originally from India but has since passed into the lore of many cultures. It goes like this. Once upon a time, some blind men are introduced to an elephant for the very first time. The first grasping the elephant's tail declares it to be like a brush. The second putting his arms around one of its legs, claims it to be a tree. Yet another feeling the trunk, confidently announces an elephant is like a snake. The fourth holding the ears, describes the elephant as a sheet of leather. None of their opinions are entirely wrong, the men have just approached the animal from different angles. As each blind man feels his way around the whole of the elephant, they discover that there is truth in what each other had said.

Gorillas and monkeys may not be as elegant as an equation but they add some colour to what can be a fairly dry subject. They form two of the elements of the My Many Me's theory. This theory proposes that different parts of our brains have different agendas and they compete to control our behaviour. How hard they push or pull are based on thought processes optimised for an environment very different to our current one and hence our behaviour often appears irrational. Applying a more primitive mentality to a situation often gives us an insight into why we behave the way we do. Well, that's the grey matter of the idea. My Many Me's evolved from this into a set of five characters or "me's" that appear in a series of comics in full 24 bit colour.

These characters are used to explain our motivation to do a particular thing over everything else. At any given time we are subconsciously applying the Procrastination Equation to all the different things we could do. Each monkey or gorilla represents a motivation or de-motivation and each is working out his or her own answer to the equation. Whoever comes up with the biggest number wins and gets to decide what we do. It's a tug of war between all our monkeys and gorillas as they pull or push us in all directions like invisible forces.

A Grand Unified Monkey House

If a theory such as the Procrastination Equation predicts whether we choose not to do a task, then the flip side says that it also predicts when we will do it. Since we either do or we don't, ergo, it must predict all our behaviour, not just the stuff we put off.

At any given time, there are almost an infinite number of things we could be doing. We clearly don't evaluate all of them all the time otherwise there wouldn't be any time left to act. So have developed the ability to stick our heads in the sand - especially the stuff that will lead us down a path to a place that we know we don't want to be. We really don't dwell too hard on how the chicken legs in the supermarkets end up in neat cellophane packs of six or that there's nothing surgical about a surgical military strike.

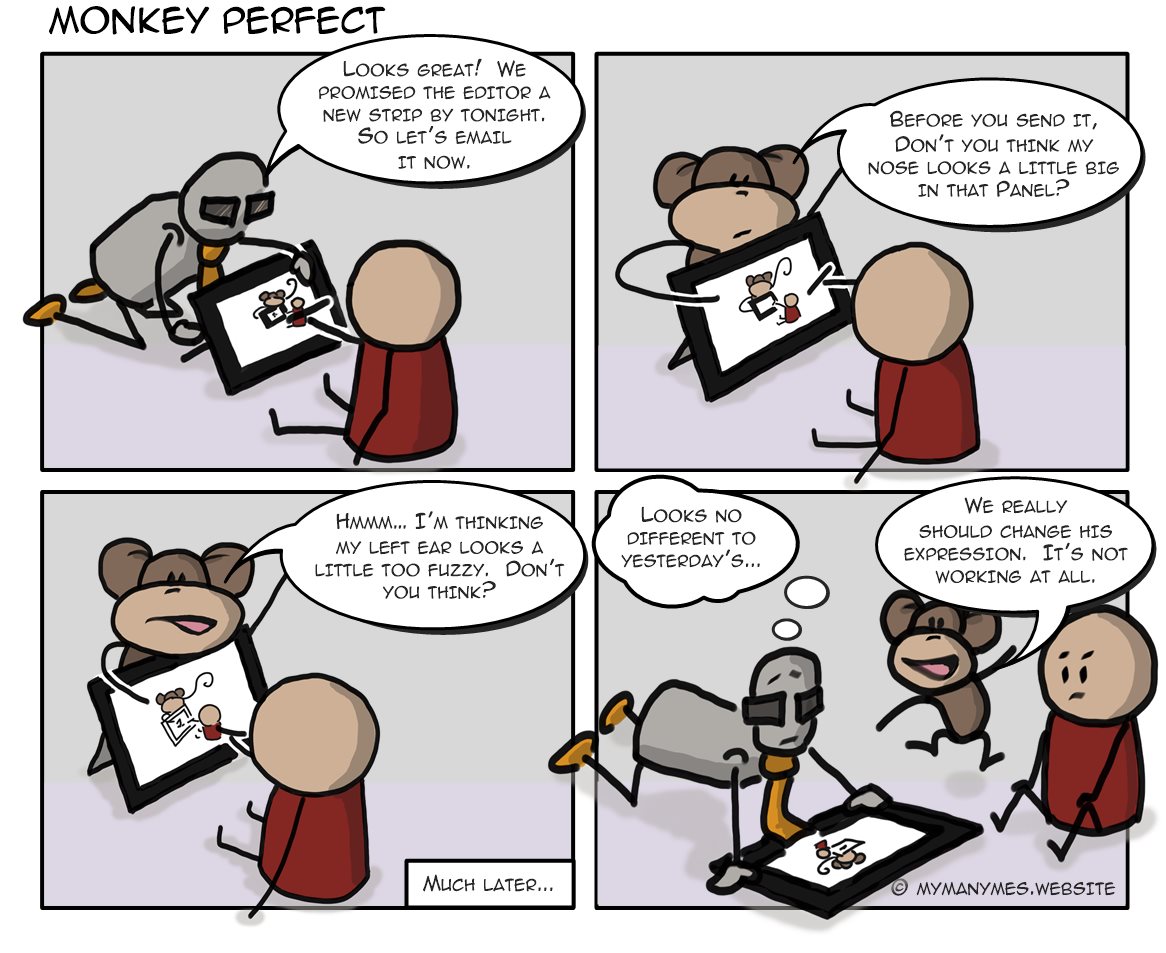

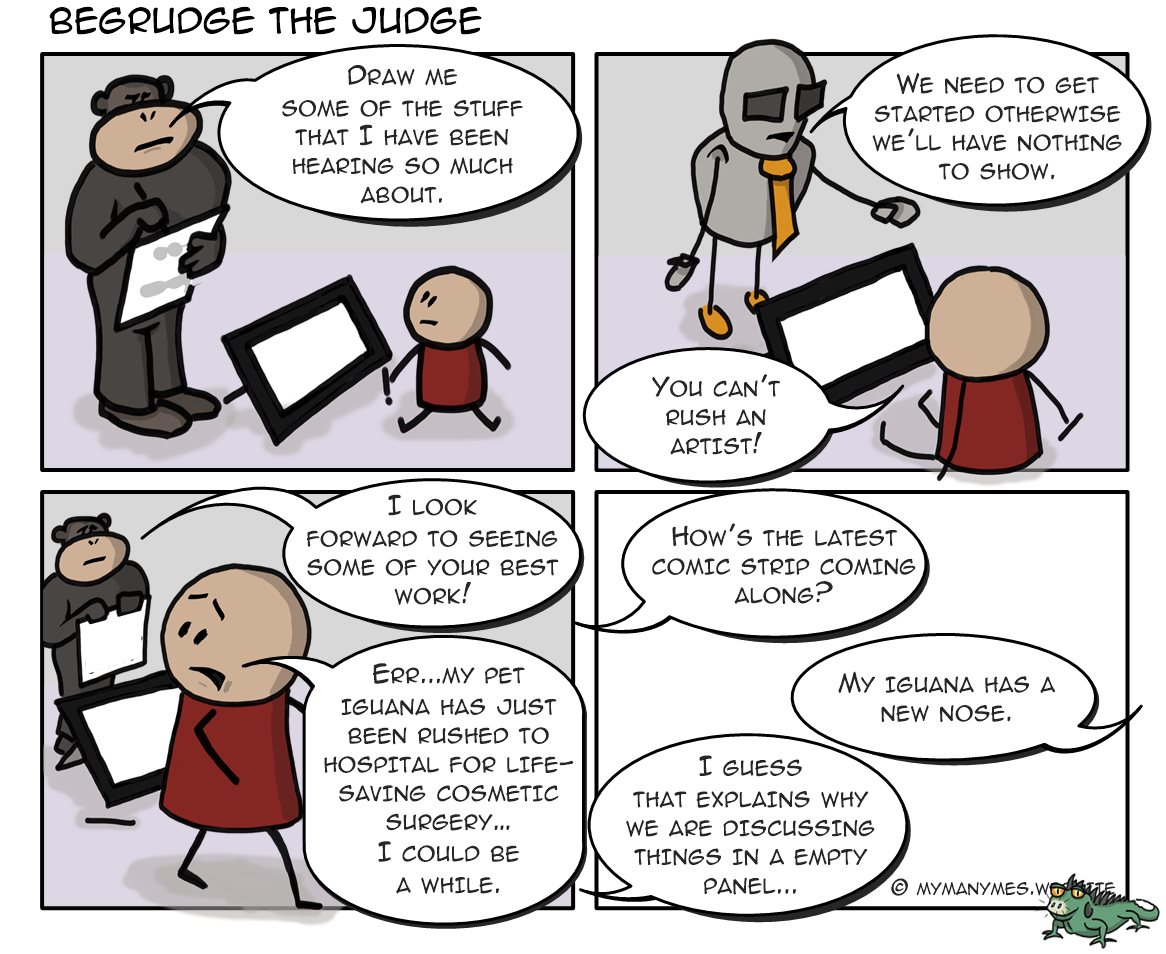

Piers Steel does not attempt to explain perfectionism and fear using the Procrastination Equation. Nevertherless our emotions do affect our motivation and hence our behaviour. Thus any emotion could lead to procrastination given a particular set of circumstances. In fact, even rational thought plays a part in procrastination through rationalisation. For example, I can convince myself that booking a flight late is the best course of action because there may be a last minute deal. But if I am brutally honest, I just want to watch a movie on Netflix instead of trawling through the Internet looking for the best option. I am not just involving my base desires or the limbic system of my brain, I am also enlisting the help of my rational side i.e. the part of my brain responsible for it, the prefrontal cortex.

The above example is perfectionism as an indulgence. We may delay sending something out in order to spend a little extra time trying to find just the right word or expression while knowing full well that it will make little difference to the recipient. It often affects creative tasks such as writing or design and is a distraction stemming from the short term gratification we experience from small incremental improvements. Something that would appear in the value parameter of the Procrastination Equation with a fairly small subjective value but exaggerated by its short delay.

Another form of perfectionism is fear of failure in the eyes of another person. Whatever result we deliver, it will not be seen as good enough. Risk taking and directness are generally viewed as positive traits in the West but in some Eastern cultures, "loss of face" drives a lot of behaviour. In Japan, people do not say "no" such is their aversion to direct rejection or disagreement. Even in the West where we are happy to directly disagree with someone, we still yearn to be accepted. Human beings have evolved to be social animals and we live in fear of rejection. It is built into the way we think even though most of the time we are not conscious of it. It is expressed in how we dress, what we say and how we say it. In fact, we are most aware of this when we meet people from other cultures who do not follow our rules of accepted behaviour. Sometimes it can be very hard to adjust - so ingrained is our culture into the way we think.

Fear is an aversion to an unwanted outcome. Or to put it another way, it is simply a desire for a different one. Either way it can be represented by a negative component in the value factor of the Procrastination Equation.

This brings us onto the issue of probability and how likely we expect an unwanted outcome to happen. This in turn determines how much emphasis we place on it. Unfortunately, statistics fails to be intuitive much beyond the single flip of a coin. Once we start pulling different coloured balls out of bags or choosing prizes behind closed doors, it all starts to get pretty muddy. So how do we determine the actual risk of an outcome in the complex real world? The answer is that we don't. Even our most powerful computers struggle to predict the weather accurately. Instead, we simplify. If we see a coin come up heads three times we instinctively expect it will come up heads the fourth time unless of course we were paying attention at school and know that the flip of an normal coin is unrelated to previous results. We are swayed by past experience and what we have been informed has happened before. Therefore, we worry unduly about very low probability events that we hear and read about. This frequently creates a highly negative motivation for certain actions. For example, we may avoid downtown because there has been a terrorist attack in another city in another country. In actual fact, an accident enroute is far, far more likely to kill us.

One could argue that neither of the above examples are cases of pure perfectionism but they are situations where the goal is higher than required. Salvador Dali once said "Have no fear of perfection - you'll never reach it." If absolute perfection is unattainable, then let's fall back onto the less perfect definition.

Hierarchy of Excess

The world is changing rapidly in a way that procrastination is likely to get worse not better. The West is enjoying a period of unprecedented prosperity but where is this all heading? The American psychologist Abraham Maslow proposed a "hierarchy of needs" where innate human needs are fulfilled in priority; physiological, safety, social, self-esteem, and finally self-actualisation. Society naturally looks to supply these needs in this order and a successful one inevitably creates an oversupply. This thus creates an "hierarchy of excess" that adversely affects the members of the society in the same sequence as the hierarchy of needs. For example:

Physiological e.g. we don't want to go hungry.

- Food and drink - abundance of sugar/fat food leads to obesity and lower life expectancy.

- Sex - unlimited access to porn affects real relationships.

- Alcohol, smoking, and drugs leads to physical addiction.

Safety Needs e.g. we want to be healthy and comfortable.

- Shelter - Unsustainable cost of care of this generation as it ages that will be carried by future ones.

- Health - The high cost of bringing new drugs to the market.

- Safety - Disproportionate actions to mitigate negligible risks e.g. food waste disposed instead of being distributed.

- Safety - Litigation over trivial incidents.

Social Needs e.g. we want to be loved.

- Friends - Social networking leading to superficial relationships e.g. Facebook/Instagram "friends".

- Interaction - Multiplayer games can be addictive.

Self-Esteem e.g. we want to feel important.

- Recognition - Authors writing blogs and articles about trivial news or rehashing existing information (e.g. what we had for lunch or tips on how to beat procrastination).

- Respect - Games that offer numerous scoreboards so everyone is a winner. Almost all games are unproductive.

- Offence - Political correctness.

Self-Actualisation e.g. we want to do good.

- Environment: Initiatives that make people feel good but have not been thought through properly so they don't actually help or they are abused e.g. diesel incentives, biofuels, green credits, certain types of recycling

The start of the 21st century has seen the Internet feed our addiction to non-physiological needs. Media and technology companies know how to keep us logging in for more, in the same way food manufacturers have learnt how to create products that we cannot stop eating. Distraction is a main driver for procrastination and is creating unnecessary stress in our modern lives.

Mind Candy

We all know we have an unhealthy eating problem in the developed world but we have yet to figure out how to deal with it. We have tried and the list of things we should avoid is getting so long that there's really no point in following it. Of course, we just need to do things in moderation but that's something we are not hardwired to do. Instead of relying solely on our fallible self-discipline, we need to work with our natural inclinations and feed the ones that work for us and starve the ones that don't.

My Many Me's and the Procrastination Equation help us identify specific causes and the most effective solutions are those that target the underlying causes. No one has come up with a single foolproof method to cure procrastination. No one has devised a diet that works for everyone either. The real world offers too much temptation so it's not really possible in a single post to add much to what has not already been covered by many other posts giving advice and tips. The key takeaway here is that we need review the reasons for our delays. Once this is done, practical steps can be found in Piers Steel's book or at the My Many Me's website.

Piers Steel tells us his advice is pharmaceutical grade. And like some of the most potent medicine, you take it because you know you need it. It's the injection, the bitter pill, the enema. However, procrastination affects almost all of us and prevention is better than a cure. In the same way, we live healthier lives by cutting down on smoking, alcohol and high fat/sugar diets. My Many Me's is what you find at the end of the aisle or next to the checkout. It's mind candy. It's the patch, the sugar coated pill, the strawberry flavoured suppository. It's a guideline to healthy thinking. You take it, not because it is medicine, you take it because you like the taste.

You can find out more about My Many Me's at www.mymanymes.website.

* an asterisk at the end of a link means that if you click this link you will be taken to another site.